This

is how we got to McMurdo on August 17 (need I say more?)

This

is how we got to McMurdo on August 17 (need I say more?)

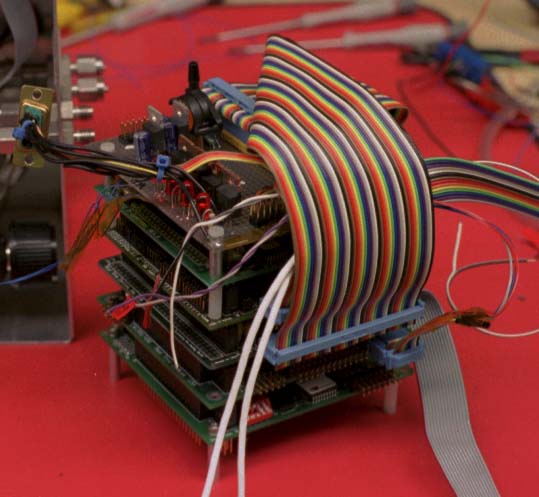

This

is the computer that we used to reduce the weight and power consumption

of our data acquisition system. It isn't better than the one we used in

Kiruna, but it sure is smaller! We had to build a special interface board

(seen here on the top in the same size format as the PC-104 system (RTD)

beneath). The system had 16 channels of 12-bit A/D, 8 digital output channels,

and two high-resolution counters. We didn't have time or money to design

a printed circuit board for the interface board, so what you see here was

hand soldered by Darin at McMurdo only days before the launch (field work

is so fun!). Fortunately, the circuit was simple enough that it worked

without much debugging. It is so dry in Antarctica that one has to use

anti-static mats (although bad practice, we often get away without them

in the lab at Irvine), seen here as the red "background".

This

is the computer that we used to reduce the weight and power consumption

of our data acquisition system. It isn't better than the one we used in

Kiruna, but it sure is smaller! We had to build a special interface board

(seen here on the top in the same size format as the PC-104 system (RTD)

beneath). The system had 16 channels of 12-bit A/D, 8 digital output channels,

and two high-resolution counters. We didn't have time or money to design

a printed circuit board for the interface board, so what you see here was

hand soldered by Darin at McMurdo only days before the launch (field work

is so fun!). Fortunately, the circuit was simple enough that it worked

without much debugging. It is so dry in Antarctica that one has to use

anti-static mats (although bad practice, we often get away without them

in the lab at Irvine), seen here as the red "background".

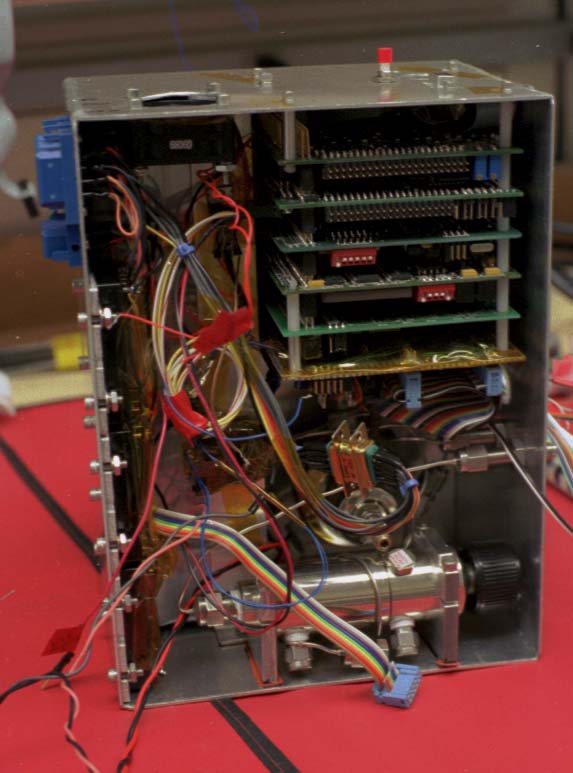

We

inserted the computer into a small box, together with the batteries (hard

to see, but upright in the back left of box), the two gas regulators, and

our DC/DC converters (on the left wall of the box). This arrangement

was not only small and lightweight, but also reduced the need for additional

heaters for the regulators because of all the heat generated by the computer,

power supplies, and batteries. The heat was just about right for the flight,

as the temperature of the box stayed well above freezing for the entire

flight. However, the balloon floated higher than we planned, and at the

low pressures, the box overheated, melting a small DC power supply on the

RTD analog board. As a result, the system stopped working on descent at

about 50 mbar. So we only have data from ascent to 20 mbar and part of

the descent.

We

inserted the computer into a small box, together with the batteries (hard

to see, but upright in the back left of box), the two gas regulators, and

our DC/DC converters (on the left wall of the box). This arrangement

was not only small and lightweight, but also reduced the need for additional

heaters for the regulators because of all the heat generated by the computer,

power supplies, and batteries. The heat was just about right for the flight,

as the temperature of the box stayed well above freezing for the entire

flight. However, the balloon floated higher than we planned, and at the

low pressures, the box overheated, melting a small DC power supply on the

RTD analog board. As a result, the system stopped working on descent at

about 50 mbar. So we only have data from ascent to 20 mbar and part of

the descent.

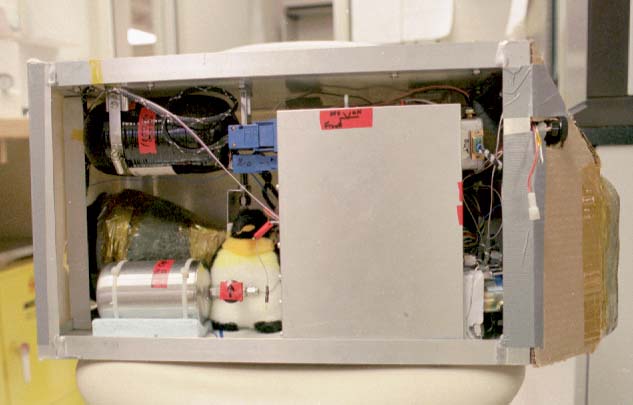

This

view shows the small box inserted into the instrument, which is about 13

inches tall. Also visible in this photo are the lightweight air bottle

(Structural Composites Industries) and the nitric oxide pressure vessel,

which was custom built by Ralph Kolbush. The penguin was purchased at Scott

Base, and it did fly (it was needed to round off the final weight of the

instrument to 18 kg). Air was pulled through the flow tube by an axial

fan housed in a fibreglass duct, seen here behind the NO pressure vessel.

This piece and the inlet (which isn't easily visible here) were constructed

by Nancy Ciszkowski, who worked in my group for a month or so in the July

of 1996 before I left for McMurdo.

This

view shows the small box inserted into the instrument, which is about 13

inches tall. Also visible in this photo are the lightweight air bottle

(Structural Composites Industries) and the nitric oxide pressure vessel,

which was custom built by Ralph Kolbush. The penguin was purchased at Scott

Base, and it did fly (it was needed to round off the final weight of the

instrument to 18 kg). Air was pulled through the flow tube by an axial

fan housed in a fibreglass duct, seen here behind the NO pressure vessel.

This piece and the inlet (which isn't easily visible here) were constructed

by Nancy Ciszkowski, who worked in my group for a month or so in the July

of 1996 before I left for McMurdo.

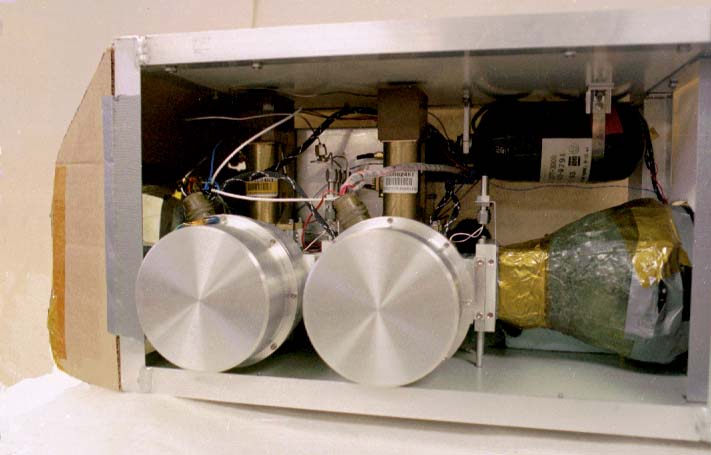

The

other side of the instrument appears here. Visible are the lamp modules,

photomultiplier tubes, and the fan duct.

The

other side of the instrument appears here. Visible are the lamp modules,

photomultiplier tubes, and the fan duct.

This

is what we went down there for. This is a typical Type I PSC that we observed

for the first couple of weeks at McMurdo. The Italian Lidar nearby told

us all we needed to determine where these were, typically between 14 and

16 km, as the air above that was probably completely denitrified and significantly

dehydrated. This photo was taken two or three hours after sunset. You can

see the wavelike structure to the "cloud" and also the characteristic violet

color.

This

is what we went down there for. This is a typical Type I PSC that we observed

for the first couple of weeks at McMurdo. The Italian Lidar nearby told

us all we needed to determine where these were, typically between 14 and

16 km, as the air above that was probably completely denitrified and significantly

dehydrated. This photo was taken two or three hours after sunset. You can

see the wavelike structure to the "cloud" and also the characteristic violet

color.

Here

is Ethan Dick's photo of the inflation of the 160,000 cubic foot balloon

that was needed to launch this 50 kg (payload and load line) up to 30 km.

The local time was about 12:00, and there was absolutely

no wind (although we could have launched if it was windy).

Here

is Ethan Dick's photo of the inflation of the 160,000 cubic foot balloon

that was needed to launch this 50 kg (payload and load line) up to 30 km.

The local time was about 12:00, and there was absolutely

no wind (although we could have launched if it was windy).

This

is another of Ethan's digital photos, in this case of Darin powering up

the instrument a few minutes before the launch. It was obviously a warm

day (it was about -15 C) because he isn't wearing his hood. The clothes

are NSF standard issue.

This

is another of Ethan's digital photos, in this case of Darin powering up

the instrument a few minutes before the launch. It was obviously a warm

day (it was about -15 C) because he isn't wearing his hood. The clothes

are NSF standard issue.